Queer Blood America

works by Jordan eagles — text by Ryan linkof

On October 26, 1954, the Code of the Comics Magazine Association of America (commonly known as the Comic Book Code of 1954) included a provision that declared, “Sex perversion or any inference to same is strictly forbidden.” The target of this restriction was self-evident to the artists and distributors that it most affected: homosexuality or queer people of any sort were officially verboten. Marketed to children and young adults, comics were perceived to have a unique power to corrupt, to transform, to forever alter impressionable readers, and were therefore no place for sex perverts. If this restriction was any indication, queer sexuality was simply too seductive for readers to resist. The Code was designed as a shield to protect innocent minds.

Nearly thirty years later, on March 4, 1983, the US Public Health Service issued another form of prohibition, stating that “Sexually active homosexual and bisexual men with multiple partners” would be forbidden from donating blood. The intent was unambiguous: as the AIDS crisis took root, queer sexuality was perceived to have a unique power to corrupt the blood supply, and by extension, the social body and the body politic. The blood of gay men was marked as a threat to the most powerful country the world had ever known. This restriction was designed as a shield to protect vulnerable bodies.

These two seemingly unrelated restrictions, aimed to contain the same marginal population, are connected in multiple ways, but perhaps most saliently in the power they confer upon homosexuality. Queer bodies are almost magical in the power they are perceived to yield – a destructive and horrible power that can colonize the mind and ravage the body. It’s almost as if they possess a kind of awful omnipotence – a preternatural superpower – usually only conferred upon comic book characters. The blood coursing through queer bodies would seem to have unique, and uniquely threatening, capabilities.

(Continued Below)

Having long explored the cultural and historical meanings of blood, Jordan Eagles has more recently interrogated the overlap of comic book superpowers and the awe-inspiring power of queer blood. Splashing the blood of sexually active gay men across the face of comic books, his work draws attention to the profound injustice of treating queer men as a biological threat; as a contagion that must be contained. In his works, comic book superheroes, as manifestations of American prowess and power, have been compromised by the intrusion of queer blood. The threat of HIV/AIDS is both underscored and undermined, offering a rebuke to the homophobic and serophobic policy that sustains the continued restrictions placed on sexually active gay men who seek to donate blood.

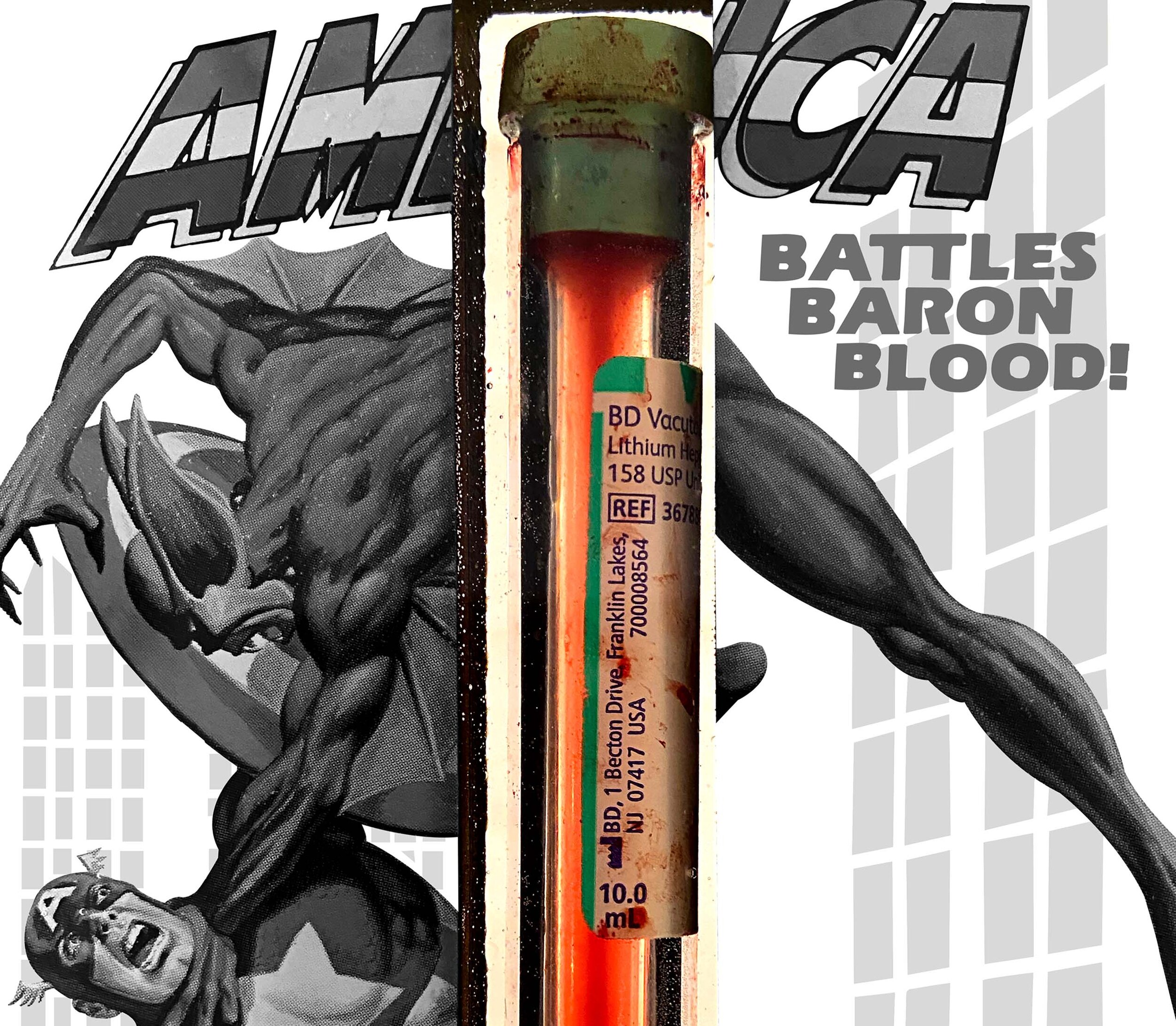

The illustrated book at the center of Queer Blood America, Captain American Battles Barron Blood!, has a particular resonance given that it was published in 1982, the year that the term “AIDS” entered official parlance and one year before the prohibition on gay men donating blood. Blood is the thematic preoccupation of the comic itself, as the beloved national hero combats the aptly named Baron Blood, a recurring vampiric foe seeking to drain the protagonist of his precious lifeforce. Ironically, the queer implications of this sinewy villain sucking the bodily fluids from a masculine icon seem to fly in the face of the restrictions on “sex perversion” that were still in place in 1982. As scholar Ramzi Fawaz has eloquently argued, however, comics lend themselves to these kinds of readings, despite the overt restrictions on queer subject matter. The character of Barron Blood seems to combine in a single body the threat of queer deviance and the destructive and deadly power of blood.

Blood, of course, has a long history of associations with magic and superpowers. The source of life and vitality, blood also has a more horrifying power: it is evidence of a body out of sorts, sick, wounded, torn open, or even killed. Blood has the power to shock and terrify. The Comic Book Code, in fact, made special note of this, stating, “All scenes of horror, excessive bloodshed, gory or gruesome crimes, depravity, lust, sadism, masochism shall not be permitted.” The increasingly bloodless cinematic representations of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, under the studio oversight of the cautious, child-friendly Disney appear to continue this tradition. Blood, much like sex perversion, continues to be seen as a powerful evil that must be eradicated.

For the generation of gay men who have grown up in the age of AIDS, we know the power of blood implicitly. Many of us are subject to regular lab tests and examinations that involve countless vials just like the one that has been laser-cut into this illustrated book. These vials reflect the dual power of blood: they are a reminder of the terrible consequences of the disease, as well as the endurance and strength of the queer community. We know the beauty and resilience of queer bodies, even in the face of censure, violence, or ravaging disease. Queer blood connects us and empowers us.

By interpolating queer blood into a narrative of superstrength, Eagles heroicizes queer bodies. His work offers an urgent and painful reminder of the work that needs to be done, but it also reminds us of the magical, life-giving power of queer blood. Eagles has created not only a physical piece that includes actual human blood, but also animations (and NFTs) that accentuate this point. The iridescent, hallucinatory glow of the blood vile in the animations speak to the ethereal, otherworldly, and magical capacity of blood.

As Marvel introduces a gay Captain America, one wonders what kinds of powers his blood contains. Will America let Captain America donate blood? Will his blood be officially forbidden from entering the social body even if it could save lives? As the country emerges from the most dangerous and deadly pandemic in a century, one hopes that the lifegiving superpower of queer blood can once again help to heal a world in peril.

June 2021

Jordan Eagles explores the visual power and cultural uses of blood in his works. His more politically motivated series advocate for fair blood donation policies, anti-stigma, and equality. He is a co-founder of Blood Equality.

Ryan Linkof is Curator at the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art in Los Angeles. His research explores queer visual history and the intersection of art and popular culture.