works by jordan eagles

Curated by ERIC SHINER

June 10, 2020 — December 1, 2020

January 18, 2021 – June 14, 2021

With

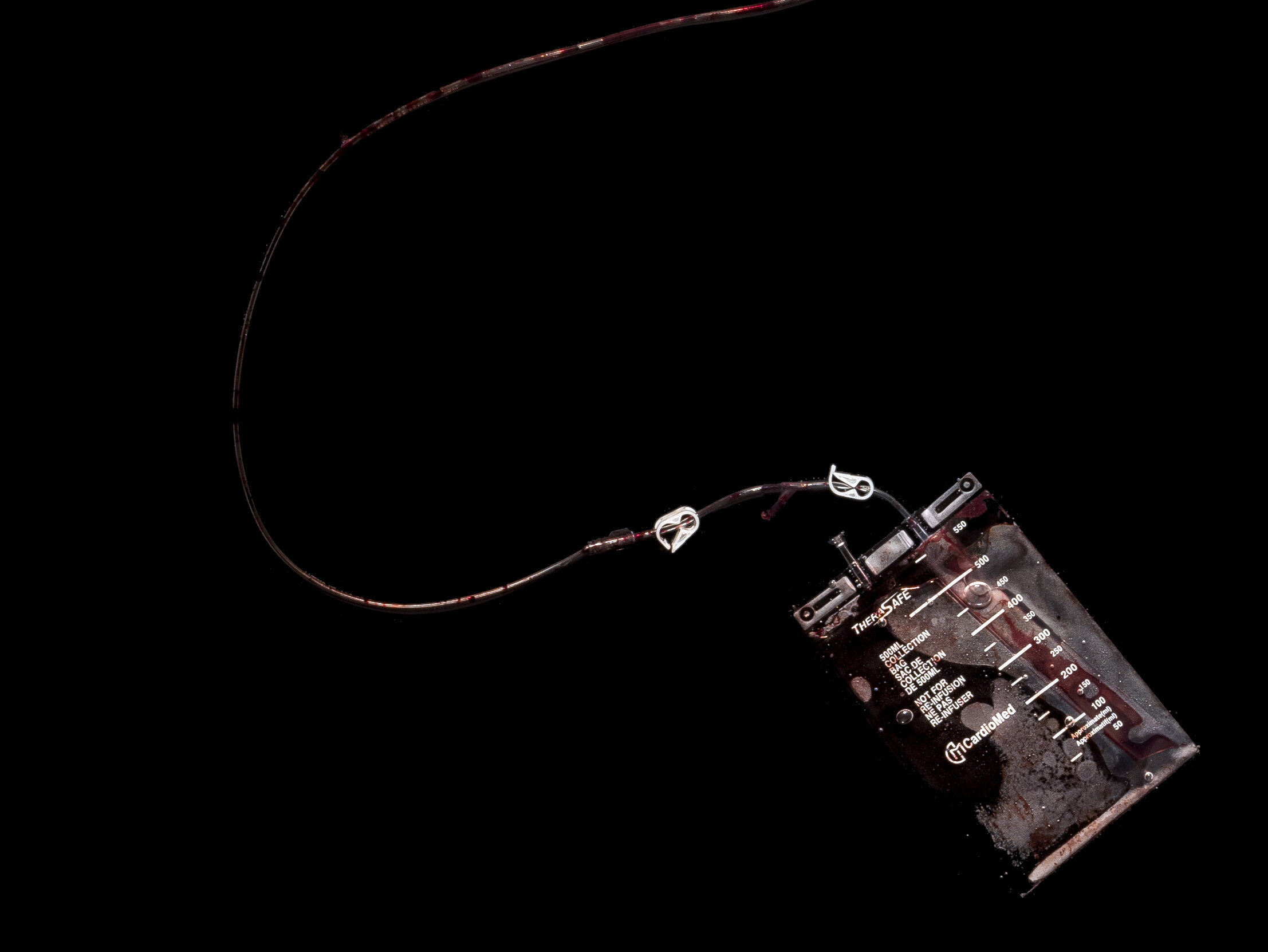

In 1983 in an early response to the AIDS crisis, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) implemented a lifetime ban on blood donations from gay and bisexual men. More than 30 years later, in 2015, the FDA updated its policy to allow gay and bisexual men to donate blood, but only if they are celibate for a full year.

In 2020, even during the COVID-19 pandemic and with massive blood shortages, the FDA continues discriminatory policies for donating blood based on sexual orientation, only allowing gay and bisexual men to donate if they are celibate for three months. There is no celibacy requirement for heterosexuals, regardless of their risk for contracting HIV.

I Am. I Am. I Am A [Super] Man.

Eric Shiner

Somewhere in a box sits a photograph of me dressed as Superman, around the age of six, happy, if not outright excited, about the evening soon to unfold. It was Halloween, of course, in the late 1970s and as a little boy in a small city in Western Pennsylvania, I felt truly invincible and empowered by my superhero costume that my mother inevitably made for me. Focused on the haul of candy to come, I was fully unaware of the future storms that I, as a man, would need to navigate and survive.

Around this time, in New York and other major cities around the globe, small numbers of gay men were falling ill and dying of a mystery disease, but the full pandemic of AIDS didn’t unleash itself fully until 1980, and then all hell broke loose. Today, forty years later, a new pandemic rages through society, terrorizing humanity and disproportionately killing African-Americans and Latinx community members as our government stumbles to help, albeit—and shockingly—a much better response than it had to the AIDS crisis when it sat idly by during the Reagan administration doing nothing at all to drive away that menace. In the face of COVID-19, the villain that befalls us now, many of us hope for a leader—a hero—that might drive out this demon. A Superman—or Superwoman—or Superperson—to find a vaccine that staves off yet another silent killer.

It goes without saying that a cure has yet to surface for AIDS four decades after it first exploded in our midst. Drug advances have allowed many infected with HIV to live full and relatively healthy lives, with many termed “undetectable.” There is also pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), which is a daily pill proven to be 99% effective in preventing HIV transmission. This is progress, but it is not a cure. Imagine the next forty years to come if a vaccine or cure for COVID-19 does not come to save us.

That’s what it is like to be a gay man of 48 years today. It has been a life filled with joy, success and celebration, just as it has been one filled with dread and neurosis that one day the virus will get me, too. Now we all share this dread with a new attacker and like before, we must do everything in our power to stop it. Stay-at-home measures have helped “flatten the curve,” but as society starts now to gradually re-emerge, widespread fears of a second wave linger in the backs of our minds, just as they did for me in the early 1990s as I was coming out as a gay man. However, today, both AIDS and COVID-19 do not discern by sexuality, having instead become tied to race and class as more determining factors.

Zap. Pow. Bang.

Flashback to 1986, the year that R.E.M., the Georgia alternative band led by gay icon Michael Stipe, releases its cover of “Superman,” originally released in 1969 by a Texas band, The Clique. The lyrics keep swirling in my head of late, as I can’t stop thinking about what or whom will save the world from the crisis that befalls us:

I am, I am, I am Superman and I know what's happening

I am, I am, I am Superman and I can do anything

If only a confident leader might espouse similar bravado to help us. If only.

I am, I am, I am Superman and I know what's happening

I am, I am, I am Superman and I can do anything

If only a confident leader might espouse similar bravado to help us. If only.

Thinking more about the meaning of these few words in 1969, in the wake of global student protests in 1968 against the war in Vietnam and the Black Power movement of the same age, a certain sense of hope is apparent amidst the chaos of the immediate. Stemming from this, I can’t help but think about the now iconic protest signs of Black Power: I Am A Man, first designed and displayed at the Memphis Sanitation Workers Strike and later used at the Poor People’s Campaign in our nation’s capital in 1968.

Where is our sign for today?

Artists are so very often the catalyst for change in society, and so many have contributed their voice and imagery to the above-discussed social movements to expose the social ills lurking behind the problems these movements endeavor to address. Contemporary artists like Glenn Ligon, Hank Willis Thomas and Kara Walker use text and image to address racism in society; collective Gran Fury, David Wojnarowicz and Felix Gonzalez-Torres took on the AIDS crisis; and Andy Warhol, Philip Pearlstein and countless others have depicted mainstream superhero characters as representations of hope and victory over evil. For our purposes here, it is the melding of these ideas that is at the heart of this essay in the form of a new project by New York City-based contemporary artist Jordan Eagles, Can You Save Superman? The work is a call to action to address an evil that persists, even in light of the fact that were it to go away, lives would be saved and new heroes minted. The evil is based not in comic books, but in policy. It addresses the reality that there are still unnecessary and discriminatory deferral periods for gay and bisexual men to be eligible to donate blood and antibody-rich plasma, due only to their sexuality. It is wrong and it must end.

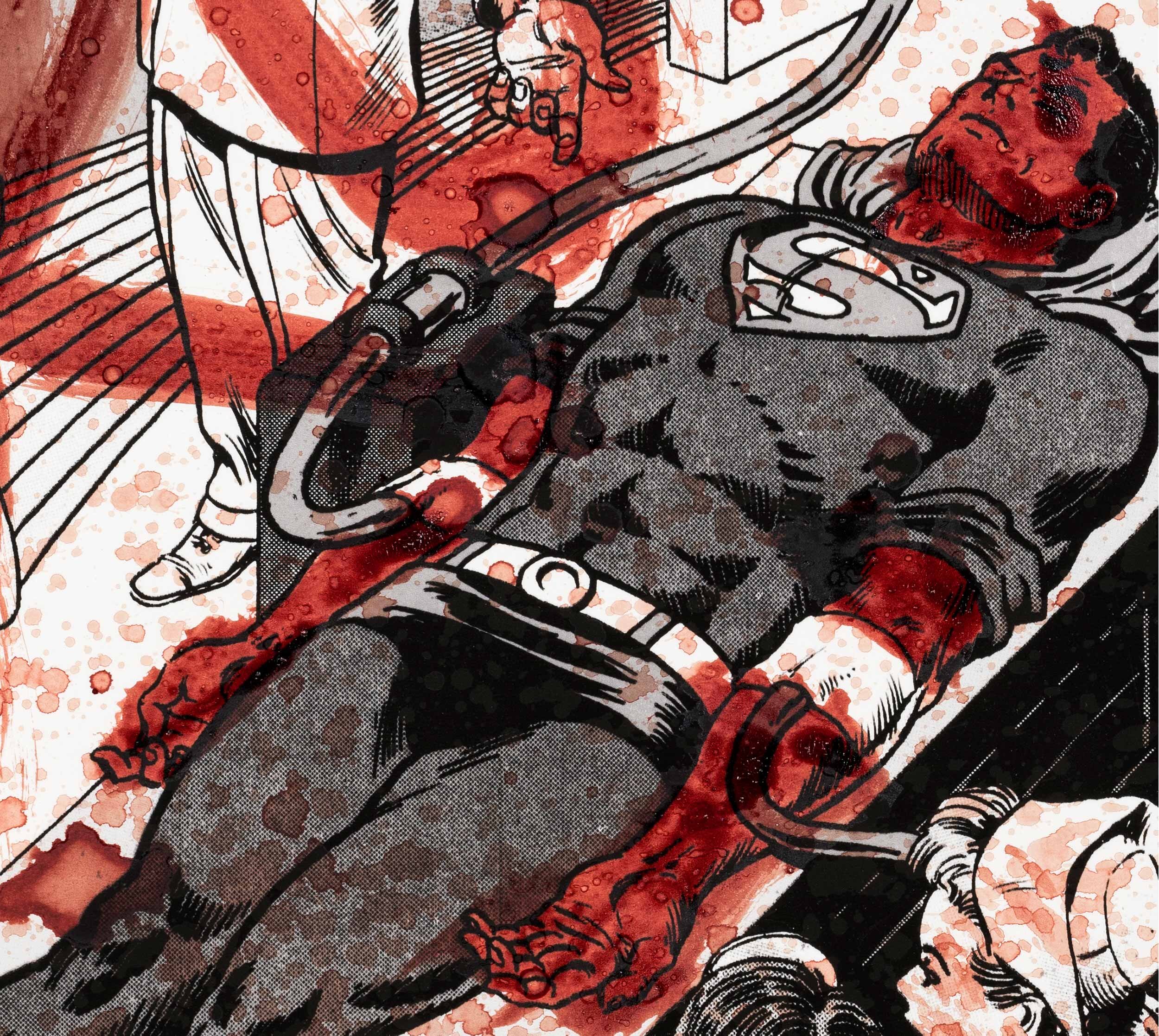

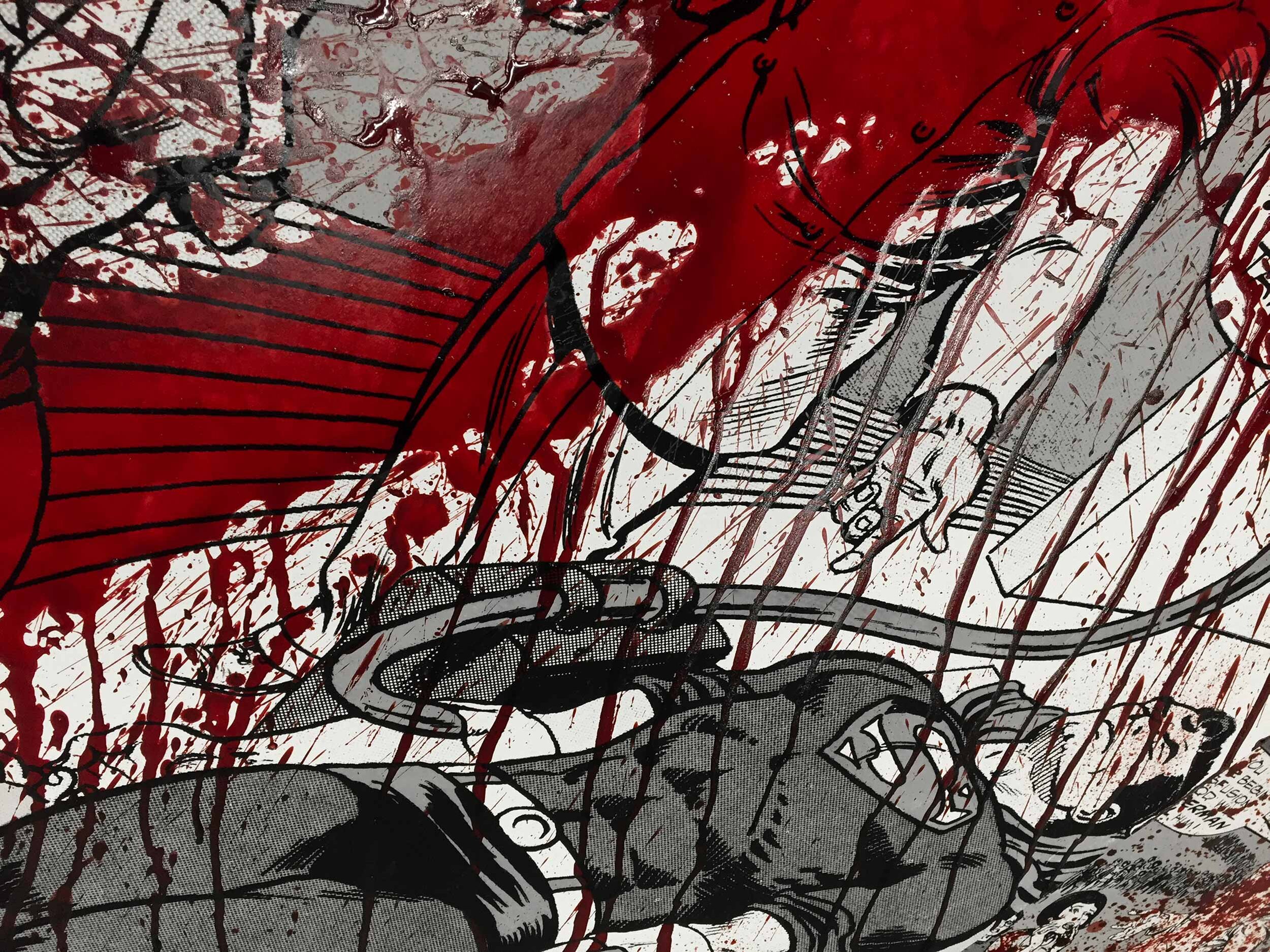

In this project, Eagles uses found images from an actual Superman comic book from 1971 entitled Attack of the Micro-Murderer. Involving heavy doses of time travel, an evil alien taking over a villain’s body to enact mayhem and the infection of Superman by a futuristic super-virus, the feel-good component of the comic features a mass call to the citizens of Metropolis to donate blood to save Superman’s life.

Sadly, the transfusion is unsuccessful, but Superman later recovers after tricking the alien to infect an android stand-in, thus ridding his own corpus of the deadly bug. Eagles uses the cover of the comic in the work at hand, splashing the blood of a gay man on PrEP as though projected onto the image. It is his way of drawing attention to the “gay blood” ban and to get us thinking about the inequalities that persist in the United States and our medical legislation, guidelines and policies.

Now, more than at any point in our lifetime, the challenges facing humanity in light of COVID-19 are fraught with life-or-death decisions that cause a wide range of emotions. Each in our own way, we hope for a fast end to this seemingly endless plague, just as we may secretly wish for a superhero to descend into our midst to rescue us from this unseeable menace. Jordan Eagles makes us realize that WE are that hero, and that collectively, we can lobby the powers that be through protest and transparency to force change to happen, just as our brothers and sisters did during the early days of the AIDS crisis and what is happening right now in streets across every major city in America, in support of racial justice.

Imagine, if you will for a moment, if YOU could save Superman. Would you help? Would you be an everyday hero and give up certain cells, antibodies, or life-giving blood? Are you legally able to do so, even if you wanted to help? Eagles forces the issue, so relevant as it is today: would you donate life-saving blood or plasma if you had positive antibodies even if you were legally able? Or would you protest the mechanisms of the law that continue to hold us down, and abstain? Of note, even though a change – albeit discriminatory – has been placed into guidelines, many close friends who have made the heroic decision to donate blood or plasma in recent weeks have been turned away upon coming out, thus feeling rejected and villainized despite their desire to simply help. This is the conundrum of our age and the focus of this timely work.

Sadly, the reality is that many who want to help fight this plague by donating blood and antibody-rich plasma are legally forbidden from doing so because of their sexual orientation. Even in the face of a global pandemic, gay and bisexual men are still precluded from donating blood and plasma due to archaic and homophobic policies that have their origins in the fear and paranoia of the early days of the AIDS epidemic.

Jordan Eagles is confronting the system by calling attention to this inequality in this all-important project launched during Pride Month, in advance of World Blood Donor Day (June 14) and through World AIDS Day (December 1). His work asks simple questions: Can you save Superman? Will you save Superman?

Although we hope that a hero comes to conquer this plague, the policies standing in the way of everyday heroes helping through blood and plasma donations must fall. Many of the organizations involved in this project can assist on that front, and I hope that you will take this opportunity to explore the many advocacy outlets available to you.

In returning to my memories of youth, of costume play, and of R.E.M., all swirling around images of Superman, I hope that Jordan’s work inspires you to find your own inner hero at this critical moment in time to join the fight for equality now—and sadly yet again.

June 2020, New York, NY

This project and the Museum stand firmly with Black Lives Matter and exist in solidarity with those calling for racial justice and an end to all forms of oppression. We acknowledge the groundbreaking contributions of Black surgeon, doctor and medical researcher Charles R. Drew, whose work made current blood banking practices possible, and who battled the racist blood donation policies in place during his lifetime. We also recognize that, in addition to the known contributions of Black persons to the field, much medical research has been advanced through the unconsenting instrumentalization of Black bodies, and essentialist constructions of race under the guise of science have underlied systemic discrimination for centuries. Now is the moment for us to use our collective voices, networks, and positions of power in real space and time, to make change and end the systematic oppression of those who have been and continue to be marginalized.

The Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art provides a platform for artistic exploration through multi-faceted queer perspectives. We embrace the power of the arts to inspire, explore, and foster understanding of the rich diversity of LGBTQI+ experiences. Created by our founders to preserve LGBTQ identity and build community, the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art acts as a cultural hub for the LGBTQ community. Our roots trace back to 1969 when Charles Leslie and Fritz Lohman held an exhibit of gay artists for the first time in their SoHo loft. Throughout the 1970s, they continued to collect and exhibit gay artists while supporting the SoHo art community. During the AIDS pandemic of the 1980s, the collection continued to grow as they rescued the work of dying artists from families who, out of shame or ignorance, wanted to destroy it. This led to the formation of the Leslie-Lohman Gay Art Foundation in 1987. In recognition of its importance in the collection and preservation of LGBTQ history, the organization was accredited as a museum in 2016. With a collection of over 30,000 objects, the Museum hosts six major exhibitions annually, offers several public programs throughout the year, publishes an arts newsletter, and maintains a research library of over 3,000 volumes. The Museum examines the juxtaposition between art and social justice in ways that provoke thought and dialogue.

Abroms-Engel Institute for the Visual Arts (AEIVA)

Art Connects. AEIVA’s mission is to provide a cultural gateway that enriches and supports accessible learning, research, and thinking for the UAB community, Birmingham, and beyond, through transformative and challenging exhibitions, engaging programming, and purposeful collecting. Open to the public since January 2014, highlights from AEIVA’s past exhibitions include Warhol: Fabricated, Willie Cole: Transformations, The Freedom Exhibition: Two Countries One Struggle, Enrique Martinez Celaya: Small Paintings 1974-2015, Jessica Angel: Facing the Hyperstructure, and David Sandlin: 76 Manifestations of American Destiny, Titus Kaphar: Misremembered, Hank Willis Thomas: unbranded. AEIVA exhibitions focus on artists of regional, national, and international significance, works from the AEIVA permanent collection, and exhibitions of student work, such as the annual graduating BFA Exhibition each spring.

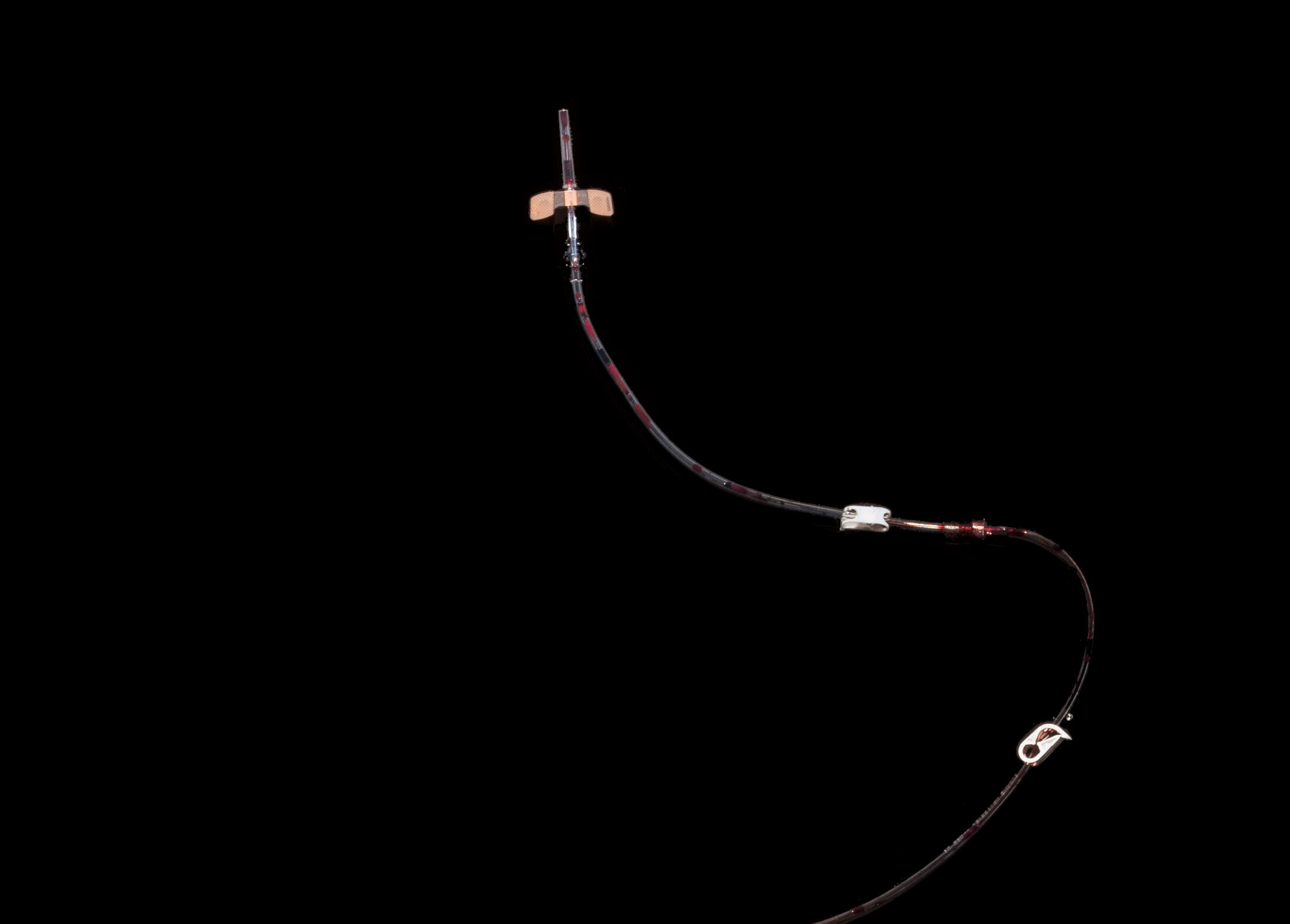

Jordan Eagles

Jordan Eagles is a New York based artist who has been exploring the aesthetics and ethics of blood as an artistic medium since the late 1990s. The themes of his work vary depending on the series and source of the blood. Eagles' works made with donated blood from the LGBTQI+ community advocate for fair blood donation policy, anti-stigma and equality. His works created with animal blood from slaughterhouses address life cycle, corporeality, spirituality, and regeneration. Eagles' exhibitions, installations and public programs include The Andy Warhol Museum (Pittsburgh, PA), Museum of the City of New York, Keith Haring Bathroom at The Center (New York), High Line (New York), Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art (New York), Birmingham Civil Rights Institute and Abroms-Engel Institute for the Visual Arts (Alabama), Science Gallery London and Melbourne, Hammer Museum (Los Angeles), Trinity Wall Street (New York), and American University Museum (Washington, D.C.). Eagles collaborated with the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene on NYC Blood Sure and is a co-founder of Blood Equality.

Eric Shiner

Eric Shiner is Executive Director of Pioneer Works in Red Hook, Brooklyn. From 2011-2016, he was the Director of The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, after serving as the Milton Fine Curator of Art at the museum beginning in 2008. He was most recently the Artistic Director at White Cube Gallery here in New York. Prior to that he served as the Senior Vice President of Contemporary Art at Sotheby's. Throughout these experiences, Eric has demonstrated his commitment to lead in ways that promote diversity, inclusion and social justice. He is president of the board of Visual AIDS and also serves on the board of City Of Asylum in Pittsburgh.

Special Thanks to:

Oliver Anene, Rehema Barber, Paul Barrett, Kat Bishop, Wayne Burns, Walker Brockington, Scott Campbell, Gonzalo Casals, Michael Chagnon, Jason Cianciotto, Demetre Daskalakis, Mike Devlin, Brendan Fernandes, John Fields, Peter Freeby, Melanie Grant, Stamatina Gregory, Dave Harper, Leo Hererra, Alejandro Jassan, Brent Foster Jones, Darren Jones, Fernando Lahoz, Rick Little, Gregory Locklear, Esther McGowan, Richard Morales, Edwin Ramoran, Eric Sawyer, Eric Shiner